Walk into virtually any molecular biology laboratory, open the -20°C freezer, and you will inevitably encounter a box labeled “Common Vectors” or “Lab Plasmids.” For countless students and early-career researchers, vector selection often begins and ends at this box: retrieving the first available tube bearing an ampicillin resistance marker. While this approach may suffice for straightforward subcloning tasks, it fundamentally treats plasmids as interchangeable commodities rather than the precision-engineered tools they represent. This lack of informed selection leads to predictable—yet entirely avoidable—failures when the chosen vector proves incompatible with experimental requirements.

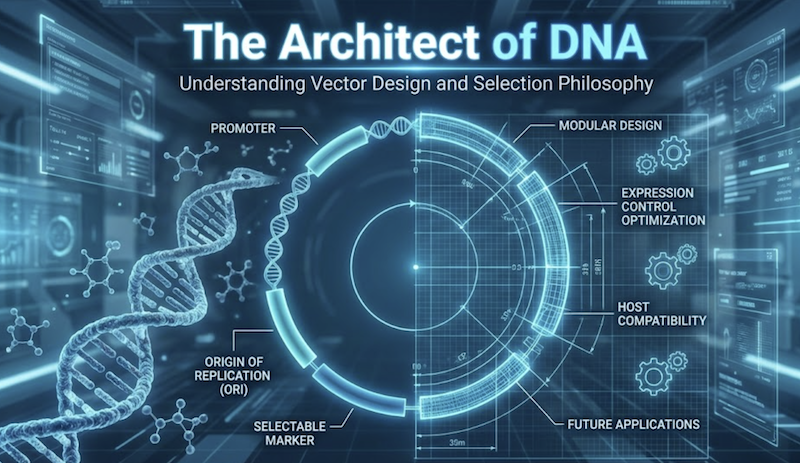

A plasmid vector is far more than a passive DNA carrier; it functions as a sophisticated molecular machine—a genetic “chassis” that dictates precisely how your insert is maintained, replicated, and expressed within the host cell. Every well-designed vector represents a carefully orchestrated assembly of functional modules: a replicon controlling copy number, selectable markers enabling transformant identification, a multiple cloning site facilitating directional insertion, and often regulatory elements governing gene expression. Each component is engineered to perform specific functions under defined conditions. The distinction between experimental success and weeks of frustrating troubleshooting frequently hinges on understanding the molecular engineering principles underlying these elements.

In this post, we advance beyond the “black box” conceptualization of plasmids to dissect their functional architecture. We will trace the evolutionary trajectory from the classical workhorse pBR322 to the streamlined, high-copy pUC series, examining the deliberate design innovations that enabled revolutionary advances like blue-white screening for recombinant clone identification. Furthermore, we will explore the strategic decision-making required to select appropriate vectors for specific experimental challenges: expressing toxic gene products that inhibit host growth, producing milligram quantities of recombinant protein for biochemical studies, or maintaining unstable genomic fragments in bacterial artificial chromosomes.

By comprehending the anatomy and engineering logic of these molecular tools, you can transition from passively “picking a plasmid” to strategically architecting experimental success—selecting vectors whose properties align precisely with your experimental objectives rather than hoping a generic choice will suffice.

Selectable Markers: Genetic “Passports” for Transformed Cells

Transformation—the artificial introduction of plasmid DNA into bacteria—is inherently an inefficient process. Even under meticulously optimized laboratory conditions, plasmids successfully establish themselves in only a small fraction of the bacterial population, typically 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻³ cells depending on the method employed. To identify these rare transformants among millions of non-transformed cells, plasmid vectors carry selectable markers—genetic “passports” that confer resistance to specific antibiotics, enabling only successfully transformed bacteria to survive and proliferate under selective pressure. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying these markers is essential not merely for clone selection, but for troubleshooting common growth anomalies and optimizing experimental outcomes.

Ampicillin and Carbenicillin Resistance (amp^r)

The most ubiquitous selectable marker in molecular cloning is the bla gene, encoding the enzyme β-lactamase. Upon expression, this enzyme is secreted into the bacterial periplasmic space via its N-terminal signal peptide. There, β-lactamase catalyzes hydrolytic cleavage of the β-lactam ring—the pharmacophore essential for antibiotic activity in penicillins and cephalosporins—thereby detoxifying the antibiotic before it can inhibit cell wall biosynthesis.

However, the remarkable catalytic efficiency of β-lactamase creates an unintended consequence, particularly when employing high-copy vectors like the pUC series. Transformants harboring these vectors secrete such abundant quantities of β-lactamase that they rapidly detoxify the surrounding culture medium, creating a protective “halo” where even non-resistant bacteria can survive. This phenomenon manifests as satellite colonies—small, untransformed colonies growing in proximity to large, genuinely resistant colonies that serve as local sources of secreted enzyme.

To mitigate this problem, many researchers substitute ampicillin with carbenicillin, a synthetic penicillin derivative. While carbenicillin functions through the same mechanism and is hydrolyzed by β-lactamase, it exhibits greater chemical stability and slower degradation kinetics. This enhanced stability maintains selective pressure for extended periods, effectively suppressing satellite colony formation. Carbenicillin is particularly advantageous for liquid cultures requiring extended incubation or for large-scale preparations where maintaining stringent selection is critical.

Tetracycline Resistance (tet^r)

In contrast to the enzymatic detoxification strategy of ampicillin resistance, tetracycline resistance operates via an active efflux mechanism. The tet gene encodes TetA, a hydrophobic membrane antiporter protein that integrates into the bacterial inner membrane. Rather than chemically modifying or destroying the antibiotic, TetA actively exports tetracycline molecules from the cytoplasm to the periplasm, coupling this transport to the proton-motive force (H⁺ gradient). By maintaining intracellular tetracycline concentrations below the threshold required for ribosomal inhibition, the cell preserves normal protein synthesis capacity.

Important considerations: The constitutive expression of TetA imposes a significant metabolic burden on the host cell, as maintaining the efflux pump requires continuous ATP expenditure. High-level TetA expression can reduce overall cell viability, decrease growth rates, and has been documented to increase negative supercoiling of plasmid DNA—potentially affecting plasmid stability and gene expression from the vector. For these reasons, tetracycline-resistant vectors may be suboptimal for applications requiring maximal host cell fitness or when plasmid topology is experimentally critical.

Kanamycin Resistance (kan^r)

Resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics like kanamycin is conferred by enzymes belonging to the aminoglycoside phosphotransferase (APH) family, most commonly APH(3′)-I or APH(3′)-II encoded by kan^r or neo^r genes. These cytoplasmic enzymes catalyze the transfer of a phosphate group from ATP to specific hydroxyl groups on the aminoglycoside molecule, chemically modifying the antibiotic and abolishing its ability to bind the bacterial 30S ribosomal subunit. This covalent modification prevents kanamycin from disrupting translational fidelity and inducing the lethal misreading of mRNA.

Advantages: Kanamycin resistance genes impose minimal metabolic burden compared to efflux-based systems, exhibit excellent stability, and maintain consistent selective pressure across diverse bacterial strains. Additionally, the kan^r marker is widely used in eukaryotic systems (as neo^r for G418 selection), making it valuable for shuttle vectors designed to function in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic hosts.

Selection Strategy Considerations

When choosing a selectable marker, consider:

- Copy number effects: High-copy vectors with amp^r may require carbenicillin or higher antibiotic concentrations to prevent satellite colonies.

- Metabolic burden: Tetracycline resistance imposes greater fitness costs than β-lactamase-based resistance, potentially affecting protein expression yields.

- Multi-plasmid systems: For co-transformation experiments, select markers from different resistance classes to enable dual selection (e.g., amp^r + kan^r).

- Host strain compatibility: Verify that your host strain is genuinely sensitive to the selected antibiotic—some lab-adapted strains have acquired cryptic resistance determinants.

- Downstream applications: Consider whether the marker will interfere with subsequent experimental steps (e.g., kanamycin selection is incompatible with certain protein purification protocols involving aminoglycoside affinity tags).

Understanding these mechanistic and practical distinctions enables rational marker selection aligned with experimental requirements rather than defaulting to whichever resistance gene happens to be present in the “common vector” box.

Here’s a polished rewrite of the pBR322 section:

The Ancestor: pBR322 and “Insertional Inactivation”

To fully appreciate the sophisticated vectors dominating contemporary molecular biology, we must examine their common ancestor. Constructed in 1977 by Francisco Bolivar and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco, pBR322 represented the field’s first truly versatile, rationally designed cloning vehicle. It constituted a major evolutionary leap—streamlining the unwieldy, poorly characterized natural plasmids of the early 1970s into a compact, precisely mapped 4,361 bp circular vector carrying two distinct selectable markers: genes conferring resistance to ampicillin (bla, encoding β-lactamase) and tetracycline (tet).

The Logic of Insertional Inactivation

Long before the advent of convenient chromogenic screening methods, researchers employed an elegant genetic logic puzzle termed insertional inactivation to distinguish recombinant clones from background. The pBR322 architecture features strategically positioned unique restriction sites located within the coding sequences of both antibiotic resistance genes. Most notably, a BamHI site resides precisely within the tet gene (at position 375 bp into the 1,194 bp coding sequence).

When foreign DNA is inserted at this BamHI site, the tet gene is physically disrupted—its open reading frame interrupted and rendered non-functional. Consequently:

- Non-recombinant transformants (harboring empty, self-religated vector): Retain intact bla and tet genes → Amp^r, Tet^r (resistant to both antibiotics)

- Recombinant transformants (carrying inserted foreign DNA): Retain intact bla but possess disrupted tet → Amp^r, Tet^s (ampicillin-resistant but tetracycline-sensitive)

The Laborious Selection Process

Identifying recombinants required a multi-step procedure termed replica plating:

- Primary selection: Plate transformation mixture on LB-ampicillin medium. All transformants (both recombinant and non-recombinant) form colonies.

- Replica transfer: Using sterile velvet cloth or nitrocellulose membrane, transfer colonies in precise spatial arrangement to a secondary LB-tetracycline plate.

- Differential growth: Incubate both plates overnight.

- Non-recombinants grow on both plates (Amp^r, Tet^r)

- Recombinants grow only on the ampicillin plate; their corresponding positions on the tetracycline plate show no growth (Amp^r, Tet^s)

- Clone recovery: Compare the two plates, identify positions where colonies appear on ampicillin but not tetracycline, then recover those recombinant clones from the master ampicillin plate.

This process was laborious, time-consuming, and required meticulous spatial mapping. A typical cloning experiment might involve screening 50-200 colonies—a full day’s work before even beginning plasmid preparation and insert verification.

Copy Number and Chloramphenicol Amplification

Unlike modern high-yield vectors, pBR322 maintains a relatively modest copy number of 15-20 plasmids per cell under standard growth conditions. This reflects its unmodified pMB1 replicon, which retains wild-type regulatory elements including functional RNA I inhibitor and Rom protein.

To obtain sufficient plasmid DNA for restriction mapping and sequencing (which required substantially more material in the pre-PCR era), researchers routinely employed chloramphenicol amplification:

- Mechanism: Chloramphenicol inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by blocking the peptidyl transferase center of the 70S ribosome. This arrests chromosomal replication, which requires continuous synthesis of initiator proteins.

- Selective amplification: Because pBR322 replication operates under “relaxed control”—depending only on stable, long-lived host enzymes (DNA polymerases, RNA polymerase, RNase H) rather than unstable plasmid-encoded proteins—plasmid replication continues unabated even as the host cell’s biosynthetic machinery is frozen.

- Practical protocol: Add chloramphenicol (typically 170 µg/mL) to mid-log phase cultures, continue incubation for 12-16 hours. Plasmid copy number increases 5- to 10-fold, ultimately comprising up to 50% of total cellular DNA.

- Result: Dramatically improved plasmid yields, transforming pBR322 from a moderate-copy vector into a high-copy platform suitable for demanding downstream applications.

Historical Significance

Despite its limitations by contemporary standards—laborious selection scheme, moderate copy number, relatively large size, and limited multiple cloning site—pBR322 represented a transformative achievement. It provided the first well-characterized, publicly available, purposefully engineered cloning vector, democratizing recombinant DNA technology and establishing design principles that would inform all subsequent vector development.

The pBR322 backbone remains present in countless modern vectors, and understanding its architecture provides essential context for appreciating the innovations that followed—particularly the revolutionary pUC series, which we will examine next.

By the early 1980s, the functional but cumbersome architecture of pBR322 yielded to the elegantly streamlined pUC series (e.g., pUC18, pUC19), developed by Joachim Messing and colleagues at the University of California. This transition represented a transformative leap in molecular cloning “user interface” design, systematically addressing nearly every limitation and frustration associated with first-generation vectors.

High Copy Number: Productivity Without Amplification

One of the most immediately impactful innovations of pUC vectors is their extraordinary copy number. While pBR322 maintains a modest 15-20 plasmids per cell, pUC vectors self-amplify to 500-700 copies per cell under standard growth conditions—a 25- to 35-fold increase in plasmid yield from equivalent culture volumes.

This dramatic enhancement stems from two specific genetic modifications to the pMB1 replicon:

- RNA II mutation: A single point mutation in the gene encoding RNA II (the replication primer) alters the secondary structure of this transcript in a temperature-dependent manner. At physiological growth temperatures (37°C-42°C), the mutant RNA II adopts a conformation that is sterically resistant to binding by RNA I, its antisense inhibitor. Because RNA I cannot efficiently “jam” RNA II folding, primer molecules successfully initiate replication at far higher frequency.

- Rom/Rop deletion: The rom gene, encoding a protein that stabilizes the RNA I-RNA II inhibitory complex, has been deleted. Without this molecular chaperone facilitating inhibition, the transient “kissing complex” between RNA I and RNA II dissociates more readily, allowing additional RNA II molecules to escape regulatory control.

Practical consequence: Researchers routinely obtain 5-10 µg of plasmid DNA from a single 3 mL overnight culture—sufficient for dozens of restriction digestions, sequencing reactions, or transformation experiments—without ever requiring chloramphenicol amplification or large-scale preparations.

The Polylinker (Multiple Cloning Site)

pUC vectors pioneered the incorporation of a multiple cloning site (MCS), also termed a polylinker—a masterpiece of synthetic DNA engineering. This short DNA segment (typically 50-60 bp) contains a dense tandem array of unique restriction enzyme recognition sequences. For example, the pUC19 MCS contains 13 unique restriction sites including EcoRI, SacI, KpnI, SmaI, BamHI, XbaI, SalI, PstI, SphI, HindIII, and others, packed into a compact 54 bp footprint.

Design advantages:

- Cloning flexibility: Researchers can select from numerous enzyme pairs to achieve directional cloning, ensuring inserts are oriented correctly for downstream applications.

- Insert excision: Because restriction sites flank both ends of any inserted DNA, the insert can be readily excised using the original cloning enzymes or alternative sites for subcloning or verification.

- Restriction mapping: The dense array of unique sites facilitates rapid restriction mapping of unknown inserts—sequential digestion with different enzymes generates diagnostic fragment patterns revealing insert size and orientation.

- Universal primers: The conserved sequences flanking the MCS enable universal sequencing primers (M13 Forward and Reverse) to sequence any insert without designing custom primers.

This modular design philosophy—embedding a versatile cloning cassette within an optimized replication backbone—became the template for virtually all subsequent cloning vector development.

Blue-White Screening: α-Complementation

Perhaps the most visually striking innovation of pUC vectors is the ability to distinguish recombinant clones by colony color—a method exploiting the elegant genetic phenomenon of α-complementation of β-galactosidase.

The Genetic System:

pUC plasmids carry the lacZα fragment, encoding the N-terminal 146 amino acids of E. coli β-galactosidase (the α-peptide). The MCS is strategically embedded within this coding sequence, positioned such that insertions disrupt the open reading frame. These vectors are designed for use with specialized host strains (such as DH5α, JM109, or XL1-Blue) that harbor a deletion of the N-terminal lacZ region but express the lacZω fragment—the complementary C-terminal portion of β-galactosidase.

The Complementation Mechanism:

Individually, neither the plasmid-encoded α-peptide nor the chromosomally encoded ω-fragment possesses enzymatic activity. However, when co-expressed in the same cell, these fragments spontaneously associate through non-covalent interactions, reconstituting a catalytically active β-galactosidase enzyme capable of hydrolyzing lactose and its analogs.

The Screening Protocol:

- Induction: Agar plates are supplemented with IPTG (isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside, typically 0.1-0.5 mM), a non-metabolizable lactose analog that induces the lac operon, ensuring high-level expression of both α and ω fragments.

- Chromogenic substrate: Plates also contain X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside, typically 40 µg/mL), a colorless compound serving as β-galactosidase substrate.

- Color development:

- Non-recombinant colonies (empty vector): Produce functional α-peptide → α-complementation occurs → active β-galactosidase hydrolyzes X-gal → releases 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-hydroxyindole, which spontaneously oxidizes and dimerizes → forms an insoluble blue precipitate → colonies appear deep blue.

- Recombinant colonies (vector + insert): Foreign DNA insertion disrupts lacZα reading frame → no functional α-peptide produced → complementation fails → X-gal remains uncleaved → colonies remain white or pale cream.

Visual distinction: Recombinants can be identified instantly upon removing plates from the incubator—white colonies against a background of blue non-recombinants. This eliminates the laborious replica plating required for pBR322-based insertional inactivation, reducing clone screening from hours to seconds.

Practical considerations:

- Incomplete blue color: Some recombinants may appear pale blue rather than white due to read-through translation or in-frame insertions that partially preserve α-peptide function. Always verify recombinants by restriction analysis or PCR.

- False positives: Occasionally, non-recombinant colonies appear white due to spontaneous mutations in lacZα. Screen multiple white colonies to ensure genuine recombinants.

- Host strain dependency: α-complementation requires hosts with the lacZΔM15 deletion (providing ω-fragment). Standard K-12 strains with intact lacZ will not support blue-white screening.

Combined Impact

The pUC series represented a quantum leap in cloning efficiency: high yields eliminating amplification steps, flexible MCS enabling diverse cloning strategies, and visual recombinant identification collapsing screening time from days to minutes. These innovations transformed molecular cloning from a specialized, time-intensive technique into a routine procedure accessible to researchers at all skill levels.

The pUC architecture became the de facto standard, with its design principles propagated into countless derivative vectors for specialized applications: expression vectors, protein purification systems, mammalian shuttle vectors, and more. Understanding pUC’s engineering logic provides the foundation for comprehending the entire ecosystem of modern cloning vectors.

While high-copy pUC vectors excel at DNA cloning, storage, and sequencing applications, they function essentially as genetic warehouses—optimized for plasmid amplification and maintenance but lacking the regulatory machinery required for controlled gene expression or specialized applications. Modern molecular biology frequently demands vectors with purpose-built architectures designed to commandeer cellular machinery or ensure stable propagation of challenging DNA sequences.

Expression Vectors: Engineering Protein Production

If your objective is recombinant protein production, the vector must “speak the language” of the bacterial transcription and translation machinery with exceptional fluency. To achieve this, expression vectors incorporate several critical regulatory elements:

1. Strong, Regulatable Promoters

Expression vectors are equipped with powerful promoters, typically derived from bacteriophages:

- T7 promoter: The most commonly used system, derived from bacteriophage T7. This promoter is recognized exclusively by T7 RNA polymerase (not by E. coli RNA polymerase), enabling tightly regulated, high-level transcription.

- T3 and SP6 promoters: Alternative phage-derived promoters useful for directional cloning strategies or in vitro transcription applications.

- lac/tac/trc promoters: E. coli-derived hybrid promoters combining lac operator sequences with strong constitutive promoter elements, enabling IPTG-inducible expression.

These promoters typically flank the multiple cloning site, serving dual purposes:

- In vitro transcription: Using commercially purified phage RNA polymerases to synthesize RNA probes for Northern blots, in situ hybridization, or ribozyme studies.

- In vivo protein overexpression: When the vector is introduced into specialized host strains (such as BL21(DE3)) that chromosomally encode T7 RNA polymerase under IPTG control, adding inducer triggers massive transcription from the T7 promoter, often achieving expression levels where the recombinant protein constitutes 30-50% of total cellular protein.

2. Optimized Ribosome Binding Sites

However, abundant mRNA is insufficient—transcripts must be translated efficiently. Expression vectors incorporate an optimized ribosome-binding site (RBS), also termed the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, positioned upstream of the initiating AUG codon. This purine-rich sequence (consensus: AGGAGGU) base-pairs with complementary sequences in the 16S rRNA of the 30S ribosomal subunit, positioning the ribosome precisely for translation initiation.

Critical design parameter: The spacing between the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and the start codon is absolutely critical—optimal spacing is 5-9 nucleotides. Deviations by even 2-3 nucleotides can reduce translation efficiency by an order of magnitude, dramatically decreasing protein yield despite abundant mRNA. Well-designed expression vectors have empirically optimized this spacing for maximal translation initiation.

3. Affinity Tags and Fusion Partners

To simplify downstream detection, purification, and characterization, modern expression vectors routinely encode short peptide “tags” fused to the N- or C-terminus of the target protein:

- Polyhistidine tags (His₆ or His₁₀): Enable single-step purification via immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) using nickel or cobalt resins. The His-tag can often be removed post-purification using engineered protease cleavage sites (e.g., TEV or thrombin recognition sequences).

- Glutathione S-transferase (GST): A 26 kDa fusion partner that enhances solubility of aggregation-prone proteins while enabling affinity purification on glutathione-agarose resin.

- Maltose-binding protein (MBP): A 42 kDa fusion tag that dramatically improves soluble expression of difficult proteins while facilitating purification on amylose resin.

- Epitope tags (FLAG, Myc, HA): Small peptide sequences (8-10 amino acids) recognized by commercially available high-affinity antibodies, enabling detection via Western blot or immunoprecipitation without generating custom antibodies for each target protein.

Practical advantage: These standardized tags eliminate months of antibody generation and purification protocol development, accelerating the path from gene sequence to purified protein.

Low-Copy-Number Vectors: When Less Is More

In vector design, maximizing copy number is not universally advantageous. Several scenarios demand deliberately reduced plasmid dosage:

1. Toxic Gene Products

Some genes encode proteins that are cytotoxic to E. coli even at low concentrations—examples include certain membrane proteins that disrupt cellular architecture, nucleases that degrade chromosomal DNA, or metabolic enzymes that deplete essential metabolites. When cloned into high-copy vectors like pUC (500-700 copies/cell), the massive gene dosage produces lethal protein concentrations, killing transformants before colonies can form.

2. Unstable DNA Sequences

Certain DNA sequences are intrinsically unstable during replication:

- Inverted repeats: Form cruciform structures that stall replication forks and stimulate recombination-mediated deletion.

- Direct repeats: Promote homologous recombination between repeated elements, excising intervening sequences.

- AT-rich sequences: Can denature spontaneously during replication, causing polymerase slippage and frameshift mutations.

- Chi sequences: Stimulate RecBCD-mediated recombination in recA⁺ hosts.

In high-copy vectors, the continuous replication stress amplifies these instability problems. Plasmids undergo deletion events—losing portions of the insert—as a survival mechanism, yielding transformants harboring truncated, non-functional constructs.

The Solution: Stringent Replicons

Low-copy-number vectors employ “stringent” replication control mechanisms, maintaining dramatically reduced plasmid dosage:

- pSC101-derived vectors: ~5 copies per cell (100-fold lower than pUC)

- p15A-derived vectors (e.g., pACYC): ~10-12 copies per cell (50-fold lower than pUC)

- BAC vectors (F-plasmid-derived): ~1-2 copies per cell (designed for cloning genomic DNA fragments up to 300 kb)

Practical outcome: By maintaining low gene dosage, these vectors enable:

- Stable propagation of toxic genes that would kill cells in high-copy vectors

- Faithful maintenance of unstable sequences without deletion or rearrangement

- Reduced metabolic burden on the host, often improving transformation efficiency and cell viability

Trade-off: Plasmid yields are proportionally reduced—a miniprep that would yield 10 µg from a pUC vector might produce only 0.5-1 µg from a pSC101 vector. However, this is preferable to obtaining zero functional clones.

Plasmid Incompatibility: The Rules of Co-Existence

Experimental designs increasingly require maintaining multiple plasmids in a single cell—for example:

- Co-expressing two proteins that form heteromeric complexes

- Using a reporter plasmid alongside an expression vector

- Performing complementation assays with rescue plasmids

- Building synthetic genetic circuits with multiple regulatory modules

However, not all plasmid combinations can stably coexist. Plasmid incompatibility represents a fundamental biological constraint: plasmids sharing the same replication control machinery (belonging to the same incompatibility group) cannot be co-maintained without continuous, stringent dual selection.

The Mechanism:

Incompatibility arises because plasmids with identical replicons compete for the same replication machinery:

- ColE1-type incompatibility: Mediated by cross-inhibition via RNA I. The RNA I transcribed from Plasmid A can bind to and inhibit RNA II of Plasmid B, and vice versa, creating a zero-sum competition.

- Iteron-type incompatibility (e.g., pSC101): The RepA initiator protein binds iterons (repeated sequences near the origin) on both plasmids, “handcuffing” them together and preventing replication initiation.

Outcome: Through stochastic replication events, some daughter cells receive only Plasmid A while others receive only Plasmid B. Without dual antibiotic selection, the population rapidly segregates into subpopulations each carrying a single plasmid type.

The Solution: Compatible Origins

To successfully co-transform and stably maintain two plasmids, you must select vectors from different incompatibility groups with distinct replication mechanisms:

Compatible Combinations:

- pUC (ColE1 origin) + pACYC (p15A origin): Fully compatible; can be co-maintained with dual selection

- pBR322 (pMB1 origin) + pSC101 (pSC101 origin): Fully compatible

- ColE1-based + F-plasmid-based (BAC): Fully compatible

Incompatible Combinations (will not stably coexist):

- pUC + pBR322: Both ColE1/pMB1-derived (functionally identical replicons)

- pUC18 + pUC19: Identical replicons despite different polylinker orientations

- Any two ColE1-derived vectors

Practical Strategy:

When designing multi-plasmid experiments:

- Select vectors with different replication origins from distinct incompatibility groups

- Use different antibiotic resistance markers (e.g., Amp^r + Kan^r) for dual selection

- Verify stable co-maintenance by periodically re-streaking on dual-selection media

- For critical experiments, confirm both plasmids are present via restriction analysis or PCR

Important caveat: Even compatible plasmids impose cumulative metabolic burden. Co-maintaining two high-copy plasmids can reduce cell viability and growth rate. Consider using one high-copy (e.g., ColE1-derived) and one low-copy (e.g., p15A-derived) vector to minimize fitness costs while maintaining adequate expression or copy number for both constructs.

1. Define Your Primary Objective

- High-yield DNA preparation (sequencing, restriction mapping, subcloning): High-copy pUC derivatives (500-700 copies/cell) are ideal workhorses, delivering abundant plasmid DNA from minimal culture volumes.

- Protein expression: Verify the vector contains essential regulatory machinery—a strong, regulatable promoter (T7, tac, or lac), an optimized ribosome-binding site with correct spacing, and ideally an affinity tag for simplified purification.

- Long-term storage or archiving: Standard cloning vectors suffice; focus on host strain selection (endA⁻, recA⁻) to ensure plasmid stability across freeze-thaw cycles.

2. Assess Biological Risk Factors

- Toxic gene products: If your target encodes a protein cytotoxic to E. coli (membrane proteins, nucleases, metabolic enzymes), abandon high-copy vectors. Instead, employ low-copy alternatives based on pSC101 (~5 copies/cell) or p15A (~10-12 copies/cell) replicons to reduce gene dosage to tolerable levels.

- Unstable DNA sequences: Inserts containing inverted repeats, direct repeats, AT-rich regions, or other structurally problematic sequences are prone to deletion in high-copy vectors due to continuous replication stress. Low-copy vectors dramatically improve clone stability.

- Large inserts: DNA fragments exceeding 15 kb are mechanically fragile. Use low-copy vectors and gentle handling protocols (no vortexing, reduced centrifugation speeds) to prevent shearing.

3. Consider the Cellular Environment

- Single-plasmid systems: Choose based on the criteria above without compatibility constraints.

- Multi-plasmid co-transformation: Rigorously verify that vectors belong to different incompatibility groups. Mixing two ColE1-derived plasmids (e.g., pUC18 + pBR322) guarantees instability and segregation—one plasmid will inevitably be lost. Instead, pair vectors with distinct origins: ColE1 + p15A (pACYC), ColE1 + pSC101, or ColE1 + F-plasmid (BAC).

- Metabolic burden: Co-maintaining two high-copy plasmids imposes severe metabolic costs. When possible, combine one high-copy with one low-copy vector to balance expression levels with host viability.

4. Match Vector to Host Strain

A vector never operates in isolation—it exists in dynamic interplay with the host strain, and this relationship fundamentally determines experimental success:

- Routine cloning: Use endA⁻ strains (DH5α, XL1-Blue, TOP10) to prevent plasmid degradation by Endonuclease A during miniprep—a nuclease that survives boiling and reactivates upon Mg²⁺ addition during restriction digestion, shredding your carefully purified DNA.

- Stable maintenance: Use recA⁻ strains to prevent homologous recombination-mediated rearrangement or deletion of inserts containing repeated sequences.

- Protein expression: Use specialized strains (BL21, Rosetta, Origami) engineered with features like T7 RNA polymerase, codon bias correction tRNAs, or oxidizing cytoplasm for disulfide bond formation.

- Blue-white screening: Requires hosts with lacZΔM15 deletion (DH5α, JM109, XL1-Blue) to provide the ω-fragment necessary for α-complementation.

- Methylation-sensitive applications: Use dam⁻/dcm⁻ strains when preparing DNA for restriction enzymes blocked by methylation or when cloning methylation-sensitive sequences.

5. Document and Verify

- Maintain accurate records: Document which vector was used, including catalog number or lab stock identifier, to enable troubleshooting and experimental replication.

- Verify by restriction mapping: Never assume a plasmid is what the label claims. Confirm identity by diagnostic restriction digest before investing time in downstream experiments.

- Sequence critical junctions: For expression constructs, sequence the promoter-RBS-start codon junction and any fusion tag regions to verify in-frame fusions and absence of mutations.

The distinction between a researcher who consistently succeeds and one who perpetually troubleshoots often reduces to this: understanding the tools rather than merely using them. By comprehending the molecular engineering principles underlying vector design—replicon function, selection mechanisms, expression regulatory elements, and incompatibility constraints—you transform from a passive protocol executor into an active experimental architect.

When you understand why pUC vectors achieve 500-copy amplification (RNA II mutation + rom deletion), you can predict when this feature becomes a liability rather than an asset. When you grasp how α-complementation works mechanistically, you can troubleshoot why your blue-white screening failed (wrong host strain, insufficient IPTG, insert didn’t disrupt reading frame). When you recognize what causes plasmid incompatibility (shared replication machinery), you can design multi-plasmid experiments that actually work.

This is the “Biotech Vantage”—the ability to see through the surface complexity to the underlying chemical and genetic logic, enabling you to make informed decisions, troubleshoot failures, and optimize success.