Introduction

In the fast-paced, high-throughput world of modern biotechnology, plasmids have become indispensable molecular tools. Researchers routinely order them from repositories, transform them into bacteria, and amplify them overnight—often without considering the intricate molecular mechanisms at play. We depend on these “molecular workhorses” for essential tasks: gene cloning, expression studies, library generation, and protein production. Yet, despite their ubiquity, experimental failures still occur.

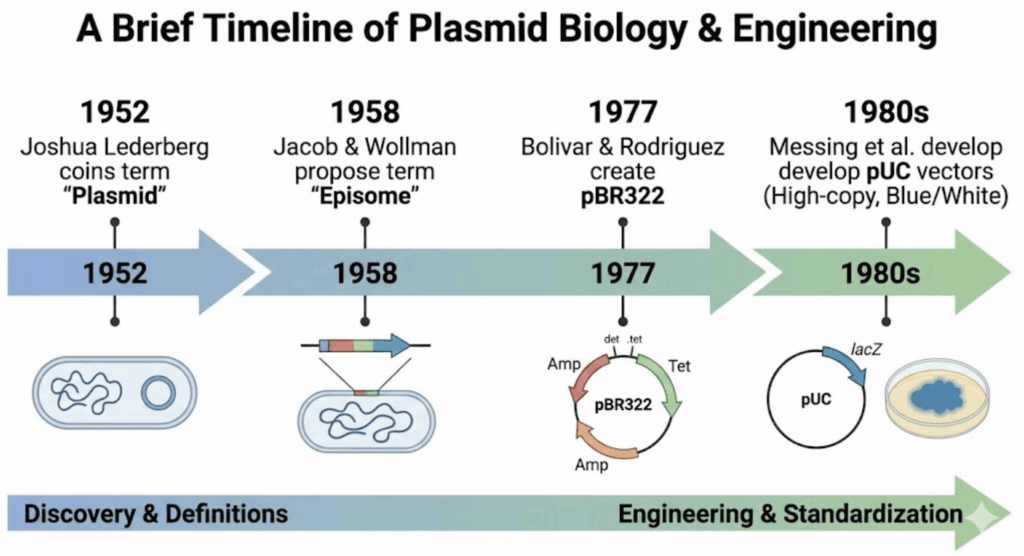

To truly master molecular cloning, understanding the foundational terminology is essential. The term “plasmid” carries significant historical weight. Joshua Lederberg and Edward Tatum coined the term in 1952 (PubMed) to describe extrachromosomal genetic elements. For years, it competed with “episome,” a term introduced by Jacob and Wollman in 1958 for genetic elements that could exist autonomously in the cytoplasm or integrate into the bacterial chromosome (PubMed).

William Hayes resolved this terminology debate in the early 1960s by standardizing the term “plasmid.” However, the distinction remains relevant: molecules that integrate into the host genome—commonly used in co-expression systems—are technically classified as plasmids, not episomes, in current usage.

Why does this historical and technical distinction matter for bench scientists today? The answer lies in understanding plasmid biology. A plasmid’s behavior is fundamentally governed by its replicon—the genetic unit controlling replication. The replicon determines critical parameters within bacterial cells, including copy number and compatibility. This knowledge isn’t merely academic; it’s essential for troubleshooting low DNA yields, addressing gene product issues, and designing effective co-expression experiments. In this article, we’ll examine these fundamental concepts in depth.

Physically, the plasmids we work with in the laboratory are distinct, remarkably stable entities. Most exist as double-stranded, covalently closed circular DNA molecules. Within their native bacterial environment, they adopt a superhelical conformation—a tightly coiled topology that renders them both compact and structurally stable. While the streamlined laboratory vectors we commonly use are relatively small (typically 3–5 kb), naturally occurring plasmids exhibit extraordinary size diversity, ranging from tiny 1 kb minicircles to massive constructs exceeding 200 kb that approach the dimensions of small bacterial chromosomes.

Despite this structural variability, all plasmids share three defining characteristics that establish their biological identity:

Independence: Plasmids are extrachromosomal elements by definition. They function as accessory genetic units, replicating and transmitting independently of the bacterial chromosome. Integration into the host genome is not required for their propagation. This physical autonomy is fundamental to molecular biology applications, enabling us to isolate plasmid DNA separately from the much larger pool of chromosomal DNA.

Host Dependence: While autonomous in replication, plasmids are entirely dependent on host cell machinery. They rely—to varying degrees—on enzymes and proteins encoded by the host genome for replication and transcription. The plasmid provides the genetic “blueprint,” but must commandeer the host’s molecular machinery (DNA polymerases, ligases, and associated factors) to execute these processes.

Host Range Restriction: Plasmids cannot replicate in just any bacterial species. Most exhibit a narrow host range, persisting only in a limited set of closely related organisms. This specificity stems from precise interactions between plasmid-encoded regulatory elements and host factors. A plasmid optimized for E. coli, for instance, will typically fail to replicate when introduced into phylogenetically distant bacteria.

These three traits illuminate fundamental aspects of plasmid biology: they are autonomous genetic entities executing their own replication programs, yet remain intimately dependent on the cellular environment they inhabit.

To understand how a plasmid functions—or why it fails—you must first understand the replicon. This concept forms the cornerstone of plasmid biology. Defined in a landmark presentation at the 1963 Cold Spring Harbor Symposium by François Jacob and colleagues, a replicon is a genetic unit comprising an origin of DNA replication (ori) and its associated regulatory elements. In essence, the replicon serves as the plasmid’s “operating system”—the minimal DNA segment capable of autonomous replication and maintenance at a defined copy number within the host cell.

Structurally, the origin of replication (ori) is a discrete DNA segment, typically spanning several hundred base pairs. It contains cis-acting regulatory elements—specific sequences that serve as binding sites for both plasmid-encoded and host-encoded factors necessary to initiate DNA synthesis. Without a functional replicon, a plasmid becomes merely an inert DNA molecule, progressively diluted and ultimately lost as the bacterial population divides.

While over 30 distinct replicons have been identified in nature, the overwhelming majority of plasmids used in molecular cloning laboratories today employ a single type: the pMB1 replicon. Originally isolated from a clinical specimen, the pMB1 plasmid carries a replicon structurally and functionally similar to the well-characterized ColE1 replicon. Through decades of genetic engineering, the ancestral pMB1 replicon has been extensively modified to eliminate regulatory constraints, yielding the high-copy-number vectors (such as the pUC series) that have become the workhorses of modern molecular cloning. These vectors excel at routine applications, generating abundant DNA yields that facilitate straightforward purification and analysis of small recombinant inserts (<15 kb).

However, high copy number is not universally advantageous. This is where low-copy-number vectors prove essential. These vectors utilize alternative replicons, such as pSC101 (maintaining ~5 copies per cell) or p15A (~10-12 copies per cell), which are indispensable for specialized applications. For example, when cloning a gene encoding a protein toxic to E. coli, a high-copy pUC vector would produce lethal protein concentrations, eliminating transformants. A low-copy pSC101 vector, conversely, maintains expression at tolerable levels, ensuring host viability. Furthermore, these replicons are critical for constructing Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs), which propagate large DNA fragments (~100 kb) that would be inherently unstable in high-copy plasmids.

| Replicon Source | Example Plasmid | Copy Number | Replication Control | Notes |

| pMB1 | pBR322 | 15–20 | Relaxed | The “classic” replicon. Often requires chloramphenicol amplification for high yields. |

| Modified pMB1 | pUC series | 500–700 | Relaxed | High copy number due to a point mutation in RNA II and deletion of the rop gene. |

| ColE1 | ColE1 | 15–20 | Relaxed | The parent of the pMB1 replicon; uses RNA I/II for regulation. |

| p15A | pACYC184 | 18–22 | Relaxed | Compatible with ColE1/pMB1 plasmids; often used for co-transformation. |

| pSC101 | pSC101 | ~5 | Stringent | Low copy number; relies on the plasmid-encoded RepA protein. Good for toxic genes. |

Selecting the appropriate replicon is therefore the foundational decision in experimental design. It determines not only DNA yield, but whether a given construct can stably exist at all.

Why do some plasmids yield micrograms of DNA from a single milliliter of culture, while others produce barely detectable amounts on an agarose gel? The answer lies in the fundamental architecture of the replicon—specifically, whether the plasmid operates under “stringent” or “relaxed” replication control. Understanding this distinction has profound practical implications for culture optimization and troubleshooting low DNA yields.

Stringent vs. Relaxed Replication

Stringent Control (e.g., pSC101): Plasmids operating under stringent control maintain low copy numbers (typically ~5 copies per cell). Their replication is tightly coupled to the host cell cycle through dependence on a plasmid-encoded initiator protein, such as RepA. RepA acts as a positive regulator at the origin of replication while simultaneously autoregulating its own expression. Because replication requires continuous synthesis of this unstable protein, DNA synthesis halts immediately when host protein synthesis is interrupted. Consequently, stringent plasmids cannot be amplified using chloramphenicol treatment—their yield remains intrinsically limited by RepA availability.

Relaxed Control (e.g., ColE1, pMB1): In contrast, the high-copy vectors that dominate modern molecular cloning (derived from pMB1 or ColE1) replicate under relaxed control. These plasmids have evolved to eliminate dependence on unstable plasmid-encoded initiator proteins. Instead, they rely exclusively on stable, long-lived host enzymes: DNA polymerases I and III, RNA polymerase, and critically, ribonuclease H (RNase H).

This reliance on stable host enzymes underlies the widely used “chloramphenicol amplification” technique. When chloramphenicol is added to a culture, it inhibits protein synthesis, arresting chromosomal replication (which requires newly synthesized proteins for initiation). However, the stable enzymes required for plasmid replication remain active. The plasmid continues replicating unchecked within non-dividing cells, accumulating to thousands of copies and ultimately comprising 50% or more of total cellular DNA.

The Molecular Switch: RNA I and RNA II

If relaxed plasmids don’t employ Rep proteins for copy number control, what prevents them from replicating uncontrollably and killing the host? The answer is an elegant regulatory system based on non-coding RNAs. In ColE1-type plasmids, replication initiation is governed by the dynamic equilibrium between two RNA transcripts: the primer (RNA II) and the inhibitor (RNA I).

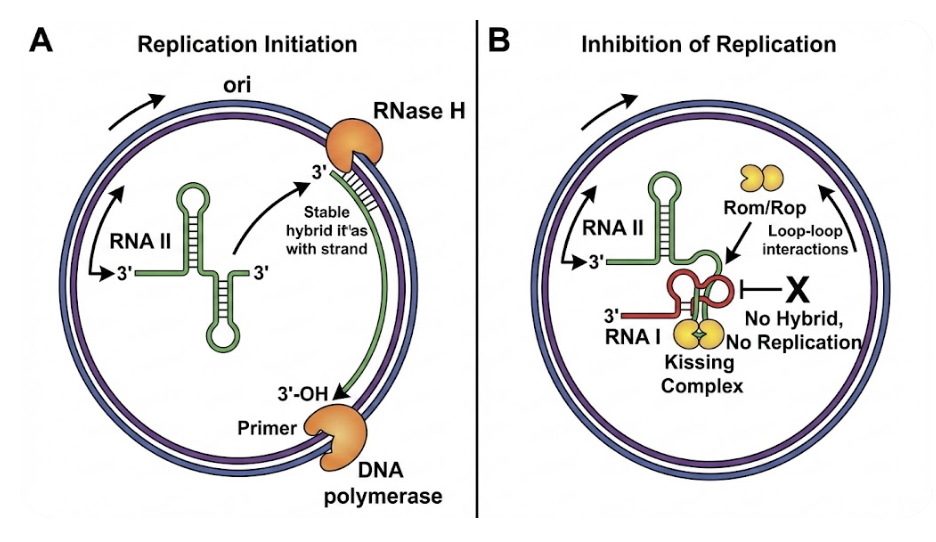

1. The Primer (RNA II): Replication initiates with transcription of a pre-primer RNA designated RNA II. This transcript originates 550 nucleotides upstream of the replication origin. As RNA II is synthesized, its 5′ end folds into a complex secondary structure, enabling formation of a stable DNA-RNA hybrid with the template strand at the origin. This hybrid serves as the essential substrate for RNase H, which cleaves the RNA at a specific site. The resulting 3′-hydroxyl group functions as the primer for DNA polymerase I to initiate leading-strand synthesis. Without proper folding and hybrid formation, replication cannot proceed.

2. The Negative Regulator (RNA I): To prevent runaway replication, the plasmid constitutively transcribes a short antisense RNA called RNA I (approximately 108 nucleotides) from the same genomic region but in the opposite orientation. RNA I is fully complementary to the 5′ region of RNA II.

The inhibition mechanism operates as a kinetic competition. RNA I binds to nascent RNA II during its synthesis, disrupting the normal secondary structure formation. This binding “locks” RNA II into an alternative conformation that cannot form the productive DNA-RNA hybrid required for RNase H cleavage, thereby preventing primer generation.

Because RNA I has a short half-life (~1-2 minutes), its cellular concentration functions as a real-time reporter of plasmid copy number. As plasmid numbers increase, the gene dosage of RNA I rises proportionally, elevating inhibitor concentration and suppressing additional replication events.

3. The Stabilizer (Rom/Rop Protein): The RNA I-RNA II interaction is further modulated by a small plasmid-encoded protein known as Rom (RNA one modulator) or Rop (repressor of primer). Rom forms a homodimer composed of 63-amino-acid subunits that fold into a precise four-helix bundle structure.

Rom binds to the initial, transient interaction between RNA I and RNA II—termed the “kissing complex“—and stabilizes this otherwise unstable pairing. By enhancing the efficiency of RNA I binding, Rom amplifies replication inhibition. This explains why deletion of the rom gene is a defining feature of many modern high-copy cloning vectors: removing this stabilizer allows RNA II to escape inhibition more frequently, dramatically increasing copy number.

In the early era of molecular cloning, obtaining sufficient plasmid DNA for analysis was a laborious process. The “classic” vector pBR322, constructed in the late 1970s, served as the workhorse of its generation. Although pBR322 carries a pMB1 (ColE1-type) replicon and replicates under relaxed control (eliminating dependence on plasmid-encoded initiator proteins), it remains subject to the regulatory constraints imposed by RNA I and the Rom protein. Consequently, under standard growth conditions, pBR322 maintains a modest copy number of only 15–20 plasmids per cell.

To generate workable quantities of DNA from pBR322, researchers relied on chloramphenicol amplification. By adding chloramphenicol to a log-phase culture, protein synthesis—and therefore chromosomal replication—was arrested. The plasmid, dependent only on stable host enzymes, continued replicating slowly over several hours, eventually accumulating to higher levels relative to the bacterial chromosome.

The pUC Revolution

The cloning landscape was transformed with the development of the pUC vector series (e.g., pUC18, pUC19). These pBR322 derivatives achieve remarkable copy numbers of 500–700 per cell without requiring chloramphenicol amplification. This dramatic enhancement resulted from two deliberate genetic modifications that systematically dismantled the plasmid’s natural regulatory mechanisms.

1. The Point Mutation in RNA II

The primary driver of the high-copy phenotype in pUC vectors is a single point mutation within the gene encoding RNA II, the replication primer. This mutation does not alter the primer sequence itself, but rather modifies its structural properties. The alteration changes the secondary structure of the RNA II transcript in a temperature-dependent manner.

At physiological growth temperatures (37°C or 42°C), the mutant RNA II adopts a conformation that is refractory to RNA I binding. Because RNA I cannot effectively bind and disrupt RNA II folding, the primer forms productive DNA-RNA hybrids at substantially higher frequency, driving rapid replication initiation. Notably, this phenotype is temperature-conditional: when pUC-containing bacteria are cultured at 30°C, RNA II reverts to a structure that RNA I can recognize, and copy number decreases to near-baseline levels.

2. The Deletion of Rom/Rop

The second modification involved deletion of the rom (or rop) gene. As described earlier, the Rom protein stabilizes the interaction between RNA II (primer) and RNA I (inhibitor). By eliminating this gene, vector designers removed the molecular “chaperone” that facilitates efficient inhibition. Without Rom, the transient “kissing complex” between RNA I and RNA II dissociates more readily, allowing more RNA II molecules to mature into functional primers. Deletion of the rom gene alone can elevate ColE1-type plasmid copy numbers by at least two orders of magnitude.

By combining a mutation that confers inhibitor resistance with deletion of the protein that enhances inhibitor function, pUC vectors achieve the extraordinary yields that have become standard in modern molecular biology—effectively converting the bacterial host into a dedicated plasmid production factory.

One of the most common frustrations in molecular biology occurs when researchers attempt to maintain two different plasmids in the same bacterial strain, only to discover that one mysteriously disappears. Despite transforming both plasmids and selecting with dual antibiotics, after several growth cycles without stringent selection pressure, one plasmid dominates while the other is lost. This phenomenon is known as plasmid incompatibility.

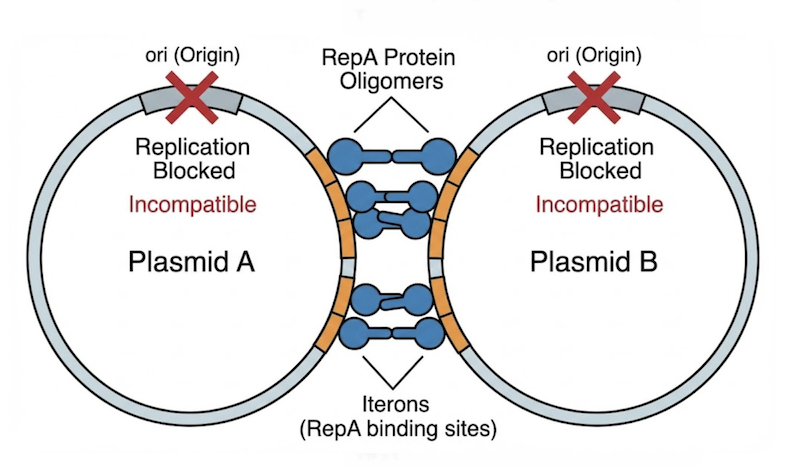

Incompatibility does not arise from direct chemical interactions between DNA molecules; rather, it represents a logistical failure within the host cell. It occurs when two plasmids share identical replication control machinery. When distinct plasmids depend on the same regulatory factors for replication initiation or partitioning into daughter cells, they are forced into competition for these limited resources—transforming replication into a zero-sum game.

The Mechanism of Plasmid Loss

The process is inherently stochastic. When two incompatible plasmids (Plasmid A and Plasmid B) coexist in the same cell, the replication machinery cannot discriminate between them and selects templates randomly. By chance alone, some cells may replicate Plasmid A more frequently than Plasmid B. As bacteria divide, this imbalance amplifies. Eventually, daughter cells emerge containing only Plasmid A or only Plasmid B. Once a cell has lost one plasmid, it cannot spontaneously reacquire it. In the absence of antibiotic selection to eliminate cells that have lost a plasmid, the population rapidly segregates into subpopulations, each carrying only a single plasmid type.

Molecular Mechanisms of Incompatibility

Different replicon families employ distinct mechanisms of incompatibility:

The ColE1 Mechanism (e.g., pBR322, pUC): Incompatibility is mediated by RNA I. When two plasmids share identical RNA I sequences, the inhibitor produced by Plasmid A can bind to the RNA II primer of Plasmid B, and vice versa. This cross-inhibition of replication makes stable coexistence impossible.

The Iteron Mechanism (e.g., pSC101): These plasmids contain repeated DNA sequences called iterons located near the replication origin. The initiator protein RepA binds these iterons to initiate replication. Incompatibility arises through a “handcuffing” mechanism wherein RepA simultaneously binds iterons on two different plasmid molecules, physically linking them and blocking replication initiation. If two plasmids share identical iteron sequences, they will mutually handcuff each other, preventing replication of both.

The Golden Rule for Co-transformation

To successfully maintain two plasmids in a single cell—for instance, to co-express two different proteins—you must adhere to the fundamental rule of compatibility: Plasmids carrying the same replicon belong to the same incompatibility group and cannot stably coexist.

The solution requires strategic pairing of plasmids from different incompatibility groups:

Incompatible combination: pBR322 + pUC19 (both ColE1-derived)

Compatible combination: pUC19 (ColE1 replicon) + pACYC184 (p15A replicon) + pSC101

By selecting vectors with distinct replication control mechanisms—such as pairing a high-copy ColE1 vector with a medium-copy p15A vector—you ensure that each plasmid maintains its own independent pool of replication factors, enabling peaceful coexistence within the cellular environment.

The theoretical principles of plasmid biology—replication control, incompatibility, and copy number—are not merely abstract concepts. They represent the variables you manipulate with every experiment you design. Understanding these mechanisms enables you to move beyond rote protocol execution toward rational experimental design. Here’s how to apply this knowledge to practical bench work.

1. Selecting the Appropriate Host Strain

The genotype of your E. coli host is as critical as the vector itself. Two specific mutations are essential for high-quality plasmid preparation:

endA Deficiency: Always use strains deficient in Endonuclease A (endA1), such as DH5α or XL1-Blue, for routine cloning. Wild-type strains (endA+) express an endonuclease that cleaves double-stranded DNA and is not completely inactivated by boiling. Consequently, when using wild-type hosts, this enzyme can degrade plasmid DNA during subsequent enzymatic reactions requiring Mg²⁺, such as restriction digestion.

recA Deficiency: To ensure insert stability, use recombination-deficient (recA1) strains. These strains lack the RecA protein required for homologous recombination. A recA1 host prevents rearrangement or deletion of cloned DNA—particularly important when inserts contain repeated sequences that might otherwise recombine with the host chromosome or other plasmid regions.

2. Optimizing Growth Conditions

Culture conditions should be tailored to the replicon your plasmid carries:

For High-Copy Plasmids (e.g., pUC, Bluescript): These vectors carry the modified pMB1 replicon and replicate constitutively. Chloramphenicol amplification is unnecessary and wasteful. Simply inoculate a single colony into rich medium (LB or Terrific Broth) and culture with vigorous aeration to late log phase. The relaxed control mechanism naturally generates high yields.

For Low-Copy Relaxed Plasmids (e.g., pBR322): When using older vectors that maintain only 15–20 copies per cell, yield can be substantially increased through chloramphenicol amplification. Add chloramphenicol (170 µg/mL) once the culture reaches mid-log phase, then continue incubation for several hours or overnight. The antibiotic arrests host protein synthesis and chromosomal replication while the plasmid—dependent only on stable host enzymes—continues replicating, dramatically increasing its cellular concentration.

3. Troubleshooting Toxic Gene Expression

Cloning failures frequently result from host toxicity when the protein encoded by the insert is deleterious to E. coli. High-copy vectors exacerbate this problem by producing elevated levels of toxic mRNA and protein, resulting in growth inhibition or cell death.

Switch Vectors: Transfer your gene into a low-copy-number vector carrying a stringent replicon, such as pSC101 (~5 copies/cell) or a p15A-based vector (~10-12 copies/cell). Reducing gene dosage often alleviates toxicity while maintaining cloning efficiency.

Switch Strains: Alternatively, employ specialized E. coli strains carrying mutations (e.g., in pcnB) designed to suppress plasmid copy number, such as ABLE C or ABLE K. These hosts reduce the copy number of ColE1-based plasmids by four- to tenfold, frequently lowering toxic protein expression to tolerable levels without requiring subcloning into a new vector.

Plasmids are often treated as simple reagents, but as we have explored, they are sophisticated molecular machines. Their behavior—whether they replicate to yield abundant DNA or vanish in competition with incompatible partners—is governed by precise, quantifiable interactions between folded RNA molecules and regulatory proteins. High yields and stable clones are not matters of chance; they are predictable outcomes of biological systems operating under defined constraints.

By understanding replicon mechanics, the elegant regulatory interplay between RNA I and RNA II, and the principles of incompatibility, you gain the power to troubleshoot experimental failures and optimize outcomes. You transition from merely executing protocols to wielding true “Biotech Vantage”—the ability to discern the molecular logic underlying each procedure.

Now that we understand plasmid architecture and intracellular behavior, the next logical step is extraction. In our upcoming post, we will shift focus from biology to chemistry, dissecting the legendary alkaline lysis method—the foundation of virtually every commercial plasmid purification kit. We will demystify those color-coded buffers, revealing the precise chemical reactions at each step that separate your plasmid from cellular debris, transforming bacterial chaos into purified DNA.

こんにちは、これはコメントです。

コメントの承認、編集、削除を始めるにはダッシュボードの「コメント」画面にアクセスしてください。

コメントのアバターは「Gravatar」から取得されます。